Book of Synergy Teil C Muscle Power Planes (2)

The development of muscle-powered flight does not really continue until November 1959, when the English industrialist and millionaire Henry Kremer offers a prize of £ 5,000 as a motivational boost for the first citizen of the British Commonwealth to fly a 1,600 m figure of eight at a height of at least 3 m using only his muscle power and without launch assistance: the famous 1st Kremer Prize.

Incidentally, Kremer is supported in his bid by a committee that muscle-flight enthusiasts at the Royal Air Force’s Cranfiel College of Aeronautics had founded in January 1957, and which a year later had merged into the Man Powerd Aircraft Group (MPAG) of the Royal Aeronautical Sociuaty (RaeS), which later also supervises the competitions and the awarding of the prize money. The implementing rules are published in February 1960. Incidentally, in 1988 the name of the group is changed to the Human Powered Aircraft Group in recognition of the many successful flights by female pilots.

Fast forward to the chronology: in February 1967 the competition is launched internationally and the prize money is doubled – and even increased to £50,000 in 1973, for again all initial attempts to meet the requirement are in vain. A slalom competition for an S-figure around three poles, also launched in 1967, fails to attract any entrants at all and is eventually withdrawn.

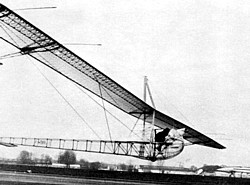

In 1959, at a cost of 30,000 DM, a glider workshop in England built a muscle-powered swing-wing aircraft with artificial feathers based on sketches by the London sculptor Emil Hartman, which the inventor appropriately named Icarus. In order to provide the necessary twisting of the wings during the flapping cycle, a special mechanical connection with a hinge joint was developed.

Of particular interest is the fact that the Icarus is launched using ‘stored muscle energy’, by means of a powerful rubber motor housed in the elongated fuselage. The stored power, together with the total energy expenditure of the pilot, is only sufficient to lift the mechanism, which is operated by hand levers and foot pedals, to flight altitudes of 3.0 – 3.5 metres. After that, however, the energy reserve is exhausted and the aircraft has to glide back to earth, gaining additional propulsion by the fluttering of the wings.

In November the ornithopter crashes at Cranfield, Bedfordshire, but is repairable and the experiments are continued in 1960, but I have not yet been able to find more details about them.

Also in 1960, Percival Hopkins Spencer proposed a four-winged ornithopter design that would provide a smoother ride for the occupants. He demonstrated the concept with the world’s first, successful, radio-controlled ornithopter. However, his proposed manned model would never be built.

Also targeting the Kremer Prize were students Alan Lassiere, Anne Marsden and David Williams at the University of Southampton, who began developing the SUMPA or SUMPAC (Southampton University Man Powered Aircraft) in 1960.

The 7.54 m long aircraft with a wingspan of 24.4 m, a wing area of 27.9m2 and an empty weight of 58.1 kg is of conventional wooden construction, with a wing structure of balsa, plywood and aluminium and a plastic covering of silver-doped parachute nylon. The two-bladed propeller is driven by pedals and chains.

Construction, in which many more students took part, began in January 1961, was awarded a grant by RAeSMPAG in February, and as early as November the first flight was made by test pilot Derek Piggott at Lasham airfield in Hampshire 64 m in a height of 1.8 m can be overcome. According to the pilot, the landing was more difficult than the take-off.

In total, the aircraft will make 40 flights, with the longest distance being a distance of 594 m at a maximum height of 4.6 m (other sources 650 m). The maximum speed is 33 km/h. However, the SUMPAC cannot fulfil the required conditions of the flight figure (lying eight) of the Kremer Prize.

In early 1963 Alan Lassiere, one of the original three initiators, takes the aircraft to Imperial College, London, for further development to better performance. While the wings were left unchanged, the fuselage is virtually completely rebuilt. Transmission is now by fabric tape, the new front section is designed from light alloy sheet and the fuselage is wrapped in Melinex (trade name of ICI’s Mylar film), which takes twice as long to design and build as the original.

In 1965, the SUMPAC is moved to West Malling in Kent, England, but before any improvement in performance can be noted, a November flight ends in disaster when pilot John Pratt aboard suddenly finds himself in a stalled aircraft at 9 m (30 ft) – perhaps due to a gust of wind. The plane crashes, destroying first the fragile structure of the wing, and then the fuselage, causing further damage.

Although Pratt was not injured, the flight tests were terminated, but the aircraft was later restored and displayed at the Solent Sky Aviation Museum in Southampton, Hampshire, where it can now be admired with a fuselage covering of transparent plastic sheeting.

Just a week after the first take-off of the SUMPAC in November 1961, another muscle-powered aircraft took off in England, also with its sights set on the Kremer Prize. In developing the Puffin I, aerodynamicist John Wimpenny, structural engineer Frank Vann, and other employees of the De Havilland Aircraft Company Ltd. at Hatfield followed a path remarkably similar to that of the Southampton team.

With the approval of Geoffrey de Havilland, the Hatfield Man Powered Aircraft Club had been formed for this purpose in 1960 – and as is to be expected from people in the aeronautical industry, design and construction are now approached with great care and attention.

With an empty weight of 58 kg, a wingspan of 25.6 m, a wing area of 30.7m2 and a propeller 2.75 m in diameter, the aircraft, made largely of balsa wood and a frame of magnesium tubes, completed over 90 flights, with John Wimpenny’s greatest distance being a straight-line distance of 908 m observed by delegates at an IATA conference who happened to be visiting the de Havilland company at the time and were now able to witness the new record.

After a crash in April 1963 with severe damage, it is decided to rebuild the aircraft, this time with a wingspan of 28.3 m and a wing area of 36.2m2, increasing the empty weight to 63.5 kg. In August 1965 the first flight of the Puffin II took place, followed by many more flights over half a mile including climbs up to 5.2 m and 180° turns, although the results were not as good as hoped.

In April 1969, the Puffin II collides with a concrete runway light post – after which the Hatfield group hands over all the remains to K. Sherwin of Liverpool University. At least the wing structure is repairable and the transmission and propeller are also salvageable.

Sherwin’s interest lies not in the Kremer Prize or setting track records, but in developing a muscle plane that can be flown on days that are not absolutely calm, and a simpler and cheaper machine that can still leave the ground. This resulted in the 63.5 kg LiverPuffin, whose wingspan was shortened to 19.5 m, which also reduced the wing area to 28.3m2.

During an attempt in December 1971, the LiverPuffin is knocked down by a gust of wind before it can make its first flight, which does not take place until March 1972, but flights of more than 20 m are not recorded.

Later, when Sherwin joins faculty of university in Singapore, he initiates corresponding student projects there, too, where two groups build one plane each – one flying and the other not. I have not yet been able to find further details on this.

From the year 1962 the HPA of the glider pilot S. W. Vine from Krugersdorp, Transvaal, in South Africa becomes known. With a similar construction to the usual single-seat powered aircraft, the machine weighs 93 kg, has a wingspan of 12.2 m and a wing area of 20.4m2. The relatively small propeller is driven by hands and feet.

But now politics is getting in Vine’s way. When he – with the Kremer Prize in mind – started building his plane in 1961, he was still a citizen of the British Commonwealth, as the regulations required. So when it was decided that South Africa would leave the Commonwealth on 31 May 1962, Vine was forced into action.

By mid-May, just two weeks before political conditions render the potential claim obsolete, the aircraft is complete but the weather is very windy and gusty, making it totally unsuitable. Vine decides to give it a try anyway. Then everything goes very quickly: the take-off into the stiff breeze, a satisfactory straight flight over about 190 m Length, a bump that pulls the plane up, the pilot loses control and the plane crashes. Vine, 70, survives unharmed, but his plane is destroyed after this first and last flight.

Around the same time, aeronautical engineering student James M. McAvoy at Georgia Tech builds an HPA with a wingspan of 16.5 m and a wing area of 26.8m2, weighing 57 kg and using a structure of aluminium and balsa wood. This machine also does not survive its first flight, as it rolls over after only 45 m on the take-off taxiway and the damage is so severe that further attempts are unnecessary.

In 1963, a student project on human-powered aircraft began at Nihon University in Japan under the direction of Prof. Hidemasa Kimura. In the course of the following years four models, LINNET I to IV, were developed.

LINNET I, considered Japan’s first HPA – and one of the best-looking HPAs ever built – makes its maiden flight with Munetaka Okamiya at the controls in February 1966, but only gets 43 m far. The wingspan of the 5.6 m long plane is 22.3 m, its empty weight 50.6 kg and the propeller is 2.7 m in diameter.

The frame is covered with styrene paper, which is made by rolling styrene resin to a thickness of about 0.5 mm like a thin sheet of metal. This material is light and also improves the rigidity of the cell. To this end, outer surface exhibits smoothness of a quality that Kimura says is far better than that of industrially manufactured Melinex, whose surface he compares to a wet paper screen.

Nevertheless, the flight performance of its successors is not much better. The model LINNET II, reduced to 44 kg weight, flies in February 1967 a distance of 91 m at an altitude of about 1.5 m, while the model LINNET III, tested in March 1970, with an increased wingspan of 25.3 m and an empty weight of 49 kg, only got 31 m far in its best flight. And even the revised version LINNET IV only managed to fly about 50 m. A project LINNET V started in 1972 was not completed. Kimura then has more success with the Egret series (see below).

Also unsuccessful is a project in Essex, whose first flight test takes place in July 1965 – although some observers claim to have seen light under the wheels during some runs. The plane has a wingspan of 27.4 m and a wing area of 37.6m2.

The original design of the Mayfly dates from 1960 and is by Brian Kerry, who was an aerodynamicist with the then Aviation Traders company. Later the design is modified by other group members and construction begins in the summer of 1961. Completion is scheduled for May 1962, but the work takes much longer than initially estimated.

After the failure, motivation wanes, and when in 1967 the bulkhead of the Nissen hut near Southend, where the aircraft is stored, collapses and damages all wing sections, the group falls apart. Only the propeller, designed by Kerry and manufactured by Martyn Pressnell, is salvaged and later used on the Toucan (see below).

British engineer and Royal Aircraft Establishment employee Daniel Perkins succeeds in a total of 97 successful ground-effect flights in July 1966 with his inflatable (!) muscle-powered aircraft Reluctant Phoenix, with a wingspan of 8.2 m and an empty weight of 17 kg, conducted within the old R100 airship hangars at Cardington.

For Perkins, his latest model is a great success, as he had already built several inflatable HPAs since the mid-1950s, none of which flew. The new version is a delta wing with a wingspan of 9.5 m and an empty weight of only 17.7 kg, whose envelope is made of polyurethane coated with nylon fabric. However, the flight capability is limited to ‘hops’ over only short distances. The longest flight is over a distance of 128 mwith a maximum height of less than 60 cm above the ground.

The unique feature of the Reluctant Phoenix is that it can be folded up and transported in the hold of a small estate car. It also survives various crashes without needing repairs, as the aircraft merely bounces when it collides with the ground. After this success, Perkins ends his involvement – and shortly after his death, the plane is handed over to Frederick E. To, another enthusiast who immediately recognizes the advantages of the system and soon begins work on a successor (see below).

The year 1967 is of special importance because, on the one hand, the Kremer Prize is now offered internationally and the prize money is doubled – and, on the other hand, several new projects start with the aim of winning it as soon as possible.

This year, for example, the Weybridge Man Powered Aircraft Group will be formed, consisting of employees of the aircraft company British Aircraft Corporation Ltd. (BAC) at Weybridge and members of the local branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society (RaeS), and begins assembling a muscle-powered aircraft at Wisley in mid-1968. Some sources date the formation of the group around P. K. Green, W. F. Ball and M. J. Rudd to 1966.

The aim of the designers is to increase the wingspan without increasing the weight. They took into account that a considerable part of the wing weight comes from structural elements which are only there to take loads, especially the torsional stresses which occur in the aileron. So the aileron is eliminated and for lateral control the whole wing is twisted from the root instead.

The resulting single-seat aircraft, named Dumbo, is a 6.4 m long low-wing monoplane with a wingspan of just under 36.7 m, a fuselage made of aluminum alloy tubes and a balsa frame covered with transparent Melinex. The empty weight is 56 kg (other sources: 80 kg). Propulsion is provided by bicycle pedals and a two-bladed pusher propeller, also made of balsa wood.

The machine flew for the first time in September 1971, with cyclist and glider pilot Christopher Lovell covering a distance of 46 m at a height of 0.9 m. The maximum speed is 25.5 km/h. In all, only two flights are made at Weybridge airfield in south London, not far from Farnborough, and these are disappointing given the wingspan.

In April 1974 Dumbo is handed over to John Potter and his group at RAF Cranwell airfield, where the aircraft is refurbished and renamed Mercury. However, this does not improve its flying qualities, as it turns out on its maiden flight in July.

Also in 1967, the Hertfordshire Pedal Aeronauts group, formed in September 1965 mainly from employees of aircraft manufacturer Handley Page Ltd. near Radlett in Hertfordshire, began to design and build a muscle-powered aircraft to win the Kremer Prize. Although the build, led by Martyn Pressnell, is funded by a grant from RaeS, it takes until 1972 for it to be successfully completed – partly because Handley Page goes into liquidation in early 1970 after sixty years as an aircraft manufacturer.

On the other hand, the Toucan was the world’s first muscle-powered two-man aircraft. The crew sits in tandem under a transparent removable canopy and uses bicycle pedals to operate the twin-bladed 3 m diameter balsa pressurised propeller mounted at the rear.

The Toucan, 8.74 m long and with a 37.5 m wide wing, made its first three flights at Radlett airfield in December 1972, with Bryan Bowen and Derek May achieving a distance of 62 m on their longest flight. With an empty weight of 66 kg (other sources: 95 kg) the plane has a take-off weight of 239 kg.

After various technical improvements in early July 1973 with a flight time of one minute and 20 seconds a distance of 640 m with an altitude of 4,5 – 6,0 m and a maximum speed of 54,5 km/h. A second flight is already finished after 311 m and both flights are limited by the exhaustion of the crew. In any case, it is not enough for the prize.

Following an accident in which the starboard wing suffers severe damage, the remainder of the year is spent on repairs, as was much of 1974. During this time, the opportunity is taken to increase the wingspan by implementing a central extension of almost 5 m. On completion of the work, the aircraft is renamed Toucan II.

With the now 109.3 kg tandem machine with a wingspan of 42.4 m and a take-off weight of 250 kg, flight tests are continued until September 1978, with the furthest distance reached in several dozen flights 457 m amounts to. And again the wing is severely damaged two more times, for which the too weak shock absorbers of the outrigger wheels are blamed.

When the Hertfordshire Group had to leave Radlett Airfield in October for refurbishment work, it was decided to bequeath the aircraft to the Shuttleworth Collection, where it would be displayed alongside its ‘ancestor’ SUMPAC.

In the same year, 1967, there are also reports of another two-seater with two propellers being built by glider developer and lecturer at the Toronto Institute of Aeronautics Wacław Czerwiński in Ottawa, Canada, but no records of any flights exist of it.

Sources look somewhat better for the muscle-powered aircraft of Horst Josef Malliga of Austria, a long-time military pilot and flight instructor who more or less single-handedly designed and built his plane. Even the wing profile is his own design. The materials used are aluminum tube spars, plywood strips and rigid polystyrene foam.

The 51.2 kg machine with a wingspan of 19.8 m is towed a few times to heights of up to 10 m – and in the autumn of 1967 the first unassisted muscle-powered take-offs take place, during which flights with distances of up to 137 m are carried out. To improve performance, the Malliga increases the wingspan to 26 m and enlarges the propeller diameter from 2 m to 2,75 m. In 1972 (o. 1973), this leads to flights of up to 350 m distance and an altitude of 1 m.

In August 1969, the muscle-powered aircraft SM-OX of Hiroshi Sato and Kenichi Maeda of Fukuoka Daiichi High School in Japan flies a distance of 30 m at a height of up to 2 m. It has a wingspan of 22 m and the empty weight is 55 kg.

Less successful at the same time is Eiji Nakamura with his machine MP-X-6, which despite a wingspan of 21 m with an empty weight of 60 kg does not take off at all.

Among the three HPAs that manage to fly in the spring of 1972, the aircraft of ex-racing driver Peter Wright stands out in particular as the first successful one-person project in Great Britain.

Wright is also the first to use carbon fibre and CF plastics, something he had learned at Rolls-Royce. He is also an active glider pilot. He had only started the designs for a fast construction in October 1969, which is an extremely short development time in the industry.

With his homebuilt, weighing only 41 kg (other sources: 43 kg), with a wingspan of 21.6 m, a wing area of 45.2m2 and a 3-blade propeller mounted at the rear, Wright succeeded in February in flights up to 275 m Distance. When the wingtips were lengthened in 1973, the wingspan was increased to 25.9 m and the area to 48.4m2.

Wright later tried his hand at a second glider, the Micron, which, however, only had a wing area of 12.5m2 with a wingspan of 23.2 m – but when it was ready in February 1976, he converted it into a single-seat high-performance glider, which subsequently served for several years at the Buckminster Gliding Club.

The second muscle-powered aircraft to take off successfully in February 1972 was named Jupiter and was built by Chris Roper of Woodford, Essex, to whom most of the information given here is also due.

In November 1959, at the age of 22, Roper had heard a radio report about the Kremer Prize – which never let go of him from then on. As early as 1961, he began his first designs (Hodgess Roper), which, however, were never built. In 1962 the design is rethought, taking into account the experience gained with the SUMPAC and Puffin aircraft, and in 1963 the design and construction of the Jupiter starts with the help of his wife Susan and others, soon to be called the Woodford Essex Aircraft Group. And this project also receives a small grant from RAeS MPAG.

It is built from 1963 to 1968, but then Roper’s ill health after an accident prevents it from continuing, and a fire also destroys part of the aircraft. In 1970 all the hardware was handed over to the then RAF Lieutenant John Potter. Under his direction, the aircraft is completed at Halton by the end of 1971 – with the help of 99 other people, including Roper himself.

Now, in February 1972, the 66.3 kg heavy airplane, which has a wingspan of 24.3 m, a wing surface of 27.9m2 and a 2.74 m diameter propeller, completes its first flight – and in June its best flights with a confirmed range of 1.070 m (and – unfortunately unconfirmed – 1.239 m in two minutes and 16.5 seconds) with John Potter at the pedals, which is celebrated as a new record, even if there is no prize for it.

Although there were also hard landings, some requiring weeks of repairs, the Jupiter became known for another first, carrying a 13.6kg payload on one of its flights, stamped envelopes bearing ‘Worlds First Man-Powered AirMail – Jupiter – 1972‘, which were sold to collectors to raise funds for the Royal Air Force Museum.

In 1974 Potter transports the Jupiter to Cranwell where further flights are made with it and the Dumbo (see above) but without further improvements. In 1978 the aircraft is transferred to the Shuttleworth Collection, where it remains until 1982, when it finds its final resting place at Filching Manor Motor Museum, Polegate, near Eastbourne in Sussex.

The third muscle-powered aircraft to complete successful flights in 1972 is the above-mentioned 2-man Toucan, which in December achieves its longest distance with 62 m its longest distance (see above).

Also in 1972, Malcolm Smith at the Northrop Institute of Technology (NIT) in Los Angeles, along with 200 students, is said to have built a two-seater MPA called Flycycle with a wing of 23.8 m span and 26.8m2 area – but no further information is available about it.

As all attempts to meet the conditions of the Kremer Prize have so far been in vain, the prize money is raised to £50,000 in 1973, equivalent to about $120,000 at that time.

In 1972, after completing the construction of a well-equipped runway 620 m long and 30 m wide, together with a hangar, on the grounds of Nihon University, Prof. Kimura directs the design of a new series of muscle-powered aircraft based on a wingspan of 22.7 m, a wing area of 28.1m2 and an empty weight of 57 kg.

A total of three Egret are built (Heron; also known as Eaglet): Egret I makes its maiden flight in February 1973 and reaches 33,8 m (other sources 154 m) and crashes in March; the revised Egret II flies Oct 153,6 m far; and Egret III manages in November 1974 a distance of 203 m. Even more notable successes, however, are achieved in a later generation with the Stork (see below).

According to reports from 1973, students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge have already been working for four years – and even with computer assistance! – on a two-seater biplane muscle-powered aircraft called BURD (Biplane Ultralight Research Device) with a wingspan of 18.9 m (other sources: 19.2 m) and a total wing area of 59.5m2, based on a so-called canard layout with front wings as horizontal stabilizers.

The essential structural analyses of many of the primary and secondary components of the BURD are carried out by Paul Hooper and Robert Peterson. However, the ability of the wings to be bent forward is neglected, with the result that the wings break away during a forward turn during the very first flight test in 1972.

Between 1974 and 1976 the BURD II is built with the same shape but with different materials. By using wing spars made of foam and graphite epoxy the weight can be reduced from 59 kg to 50.8 kg. Nevertheless it does not succeed to make the machine fly.

In 1973, the Bauer Bird biplane project by eight students from the San Gabriel Academy in California, which was partly made of PVC pipes, was equally unsuccessful – but did not take off either. Here, the span of the upper wing is 11 m, that of the lower 9.1 m, while the propeller is 2.3 m in diameter.

In the design stage at this time is another two-seat biplane with a canard layout, worked on by Prof. Karl H. Bergey at the University of Oklahoma, later co-founder of the small wind turbine company Bergey WindPower Co. (BWC), but nothing else can be found about him.

Taras Kiceniuk Jr., a student at Purdue University (?) in 1974, develops a 2-man pressurized propeller airplane that becomes known as the Icarus.

Low-wing aircraft is a ground-effect aircraft made of light alloy tubing, foam, and Mylar, with the propeller sitting directly behind the cabin on the tail boom. Kiceniuk tests the Icarus in the Mojave Desert of southern California at the same time in late 1976 that the McCready team is there to fly the Gossamer Condor (see below), and at one point the two planes even share the same hangar.

The longest flight of the Icarus takes place at Shafter Airport in August 1977, lasting over 30 seconds. However, the vehicle only gets into the air with a tow launch. Later, Kiceniuk, who also helped build the Gossamer Albatross, was part of the award-winning Bionic Bat team (see below).

Also in 1974 the 65 kg Aviette Hurel of the French aeronautical expert Maurice Hurel flies in Le Bourget 1.005,8 m far. The wingspan of the plane, which was already patented in 1945 and on which Hurel had been building since 1970, is 42 m, the length is 13 m and the diameter of the propeller is 3.7 m. The propeller is made of a special material.

Since the plane otherwise shows no special flight characteristics, is badly damaged in a strong storm, and the Kremer Prize has been won by someone else in the meantime, Hurel later donates his Aviette to an aviation museum.

Klaus Hill, who had developed the American single-seat glider Haufe HA-G-1 Buggie in 1967 together with Bruno Haufe, among others, is also reported to be engaged in the development of an aluminum-clad muscle-powered aircraft modeled on the Marske Pioneer II glider in 1974.

Unfortunately, nothing more can be found out than that the glider, which is only 3 m long and weighs 53 kg, has a wingspan of 8.8 m in tests, which was to be increased to 13.7 m in actual muscle-powered operation. Nothing is known about flights carried out.

From 1974, former USAF Lieutenant Colonel and pilot Joseph ‘Joe’ Zinno worked on a pedal-powered aircraft with his brother Clarence, financed out of his own pocket.

The 5.5 m long HPA Olympian ZB 1 with a wingspan of 23.5 m and an empty weight of 67 kg, which Zinno not only developed and above all built himself, but also supplied with energy and flew himself, managed to take off for a few seconds at the fourth attempt in April 1976 at the naval airbase Quonset Point Zinno and to fly about 23,5 m far. The ZB, by the way, stands for ‘Zinno Brothers’.

But before any further tests can be carried out, the aircraft is damaged inside the hangar by a gust of wind coming through the open door. One consolation, I suppose, is that the multi-talented Zinno is recognized by the Smithsonian and the Rhode Island Aviation Hall of Fame as the first American to fly under his own power.

Since the student team of 1975 at Nihon University is made up entirely of enthusiasts, Prof. Kimura assigns a design expert named Junji Ishii the task of developing a drastically modified HPA model, which is given the name Stork (stork).

In March 1976 the 8.85 m long aircraft with a wingspan of 21.0 m and a wing area of 28.5m2 manages to fly a distance of 203 m to fly. But then it suddenly goes a giant step further, because already in January 1977 the Nihon team manages to set up a new, official distance world record of 2.093 m with the Stork.

In 1977 work began on the Ibis, which had a similar configuration to its predecessor, but with lower wings, the tips of which were bent upwards like winglets. With the somewhat shorter, but lighter and more agile aircraft, the team finally wanted to win the Kremer Prize.

But when this record was won by another team in August 1977, they decided to continue building anyway, and the Ibis could be tested in 1978, although it turned out to be less powerful than its predecessor. The longest flight reaches 1.100 m far and lasts 2 minutes and 15 seconds. After that, Japan takes a two-year break before developing six more human-powered aircraft – as well as four muscle-powered helicopters, which I will describe in detail below.