Book of Synergy Teil C Solar energy

“All the hassle of using uranium, and all the reserves, and incidental costs like those of accidents like Chernobyl, have only given our world the equivalent of three and a half hours of solar energy.”

Helmut Tributsch

“Peacekeeping, environmental protection and security of supply are only possible through a consistent switch to renewable energies. The political mission of our age is ‘Solar for Peace'”

Gudrun Vinzig

As soon as alternative or renewable energies are mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind is the sun, and certainly for psychological reasons. The profound intermingling of the ‘sun god’ and ‘general power structures’ fields of thought has been detailed by Lewis Mumford in his extensive book Myth of the Machine. In addition, the media is also primarily concerned with solar energy – or solar power – since its useful applications are the most widespread of all alternative energies.

What makes the sun so energetically attractive is that it reliably ‘rises’ again every morning and makes its radiation available anew. The primary energy output of vertical solar radiation per square meter is 1.4 kW (solar constant). Of the radiation power of the sun at sea level, about 4 % is in the UV range (< 400 nm) and about 48 % each in the visible (400 to 750 nm) and infrared range (> 750 nm).

The total irradiation reaching the earth per year is about 1.5 x 1018 kW/h per year, i.e. 30,000 times the energy consumption of the entire human race (as of 1980). In the book Solare Weltwirtschaft (Solar World Economy ) the author Hermann Scheer assumes 16,000 times (as of 1999), presumably due to the meanwhile strongly increased global energy consumption. Other sources even talk about an energy input of only 10,000 times – but in any case it is still sufficient for all the requirements of the present and near future.

It must not be forgotten that, according to scientific findings, all fossil, non-renewable energy sources represent nothing other than stored solar energy, and that a large number of physical processes in both the micro- and macroscopic sense are directly or indirectly related to solar energy. Within the framework of the present work, however, only the direct influence or use will be considered.

In the meantime, the sun is increasingly becoming the focus of energy-economic and energy-political considerations. In addition, there is – at least among the population of the Central and Northern European industrial nations – a largely unsatisfied ‘solar instinct’, which possibly also contributes to the special attractiveness of this form of energy…

Historical review (early times until 1900)

The Omlecs were using magnetic iron parabolic mirrors as lighters in Central America over 3,000 years ago. And simple burning glasses have been found in the ruined sites of Nineveh in Mesopotamia, dating from about the 7th century BC.

Since when there are sundials – which also represent a kind of ‘solar technology’, even if not of energetic nature – is not exactly known, but it is assumed that already the prehistoric people some ten thousand years ago knew the different shadow length of rods stuck into the ground (gnomon). In any case, it is certain that the sundial was not invented by one person at a certain place, but by several people around the globe at the same time and independently of each other. The Sumerians, for example, used sundials that cast their shadows on a circular earth dial, which, however, did not yet have numerals but rather wedge-shaped markings. And the Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Chinese, and the civilized peoples of Latin America also used sundials. But back to solar energy:

Burning mirrors have been known in China since 672 BC. At that time, the eldest son was responsible for making fire for the family with a small burning mirror. In early antiquity, Socrates (469 – 399 B.C.) expounded on the passive use of solar energy in building houses. Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) proposed a method of solar evaporation of sea water for drinking. Euclid (c. 365 – c. 300 BC), in his writing on optics, pointed out the possibility of concentrating solar radiation with burning mirrors to achieve the highest temperatures. In ancient Greece, for example, the sacred fire at Delphi was lit with a burning mirror. The Romans also used burning mirrors to light fires during religious ceremonies.

Theophrastus (371 – c. 287 BC) described the method of starting a fire using reflective surfaces of glass, copper and silver. Around 230 BC, Dositheus, a friend and colleague of Archimedes, constructed a parabolic mirror that focused the sun’s rays onto a point. The first geometric representation of this mirror shape is by Diocles, 190 BC. , from his long-lost book ‘On Focal Mirrors’, the Arabic translation of which was only recovered in Iran in the 1970s.

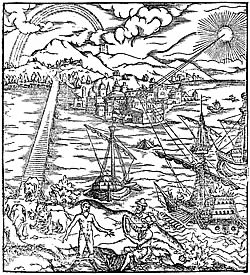

Archimedes himself (287 – 212 B.C.) is reported – be it legend or truth – to have set fire to the rigging of the Roman fleet attacking the city of Syracuse during the Second Punic War, using concentrated rays of sunlight. The copperplate engraving of the solar defensive action shown here is the title page of the Thesaurus opticus, the Latin edition of the Kitab al-Manazir, a work by the Arab scholar Abu Ali al-Hassan Ibn Al-Haitham (ca. 965 – 1040), who is also considered the inventor of the magnifying glass (see below).

In order to verify (or falsify) the report, replicas have been made over the centuries: In April 1749, Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon uses a heliostat reflector to ignite the planks of a ship from a distance of 45 m, proving that the reports about Archimedes are true. The square and adjustable reflectors he used are technically little different from the models in use today.

In 1973, the Greek Navy conducts an experiment with highly reflective bronze shields of the type Archimedes is said to have used against the Roman fleet over 2,000 years ago, and actually cause a wooden boat to burn at a distance of 50 meters.

In October 2005, members of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of Arizona recreate two of the mirror constructions possible at the time, made of bronze and glass respectively, and also attempt to use them to ignite a wooden fishing boat at a distance of 50 metres. It is worth taking a look at the picture gallery to follow the experimental setup – and the result shown here – in detail.

On 22.10.2008 another experiment is carried out there, this time with an actually also floating ship. This experiment is also successful and burns a hole in the planks.

A thesis, which is much more difficult to answer, is the assumption that the stone circles are ancient solar power plants, where the stones themselves, mirrors and the incident sunlight were used to generate whirlwinds. It is said that stretched cloth or animal skins covered with gold leaf were used as mirrors. The bundled sunlight heats the stones, which in turn release the heat into the air and create a lift, similar to that of a high-pressure area (albeit much larger). At the same time, a constant negative pressure (low pressure area) is created in the centre of the stone circle.

The updraft acts in the form of a circular wall, so that the negative pressure only has the possibility of balancing itself out from above, whereby the cold air mass sucked into the centre of the circle from above manifests itself as a vortex. (Meanwhile however, there is also contrary opinion, according to which low pressure area is maintained by pulsating change of aggregate states…. however here is not the right place to go into that subject).

There is a similar thesis concerning the pyramids. Here, solar energy had been used mainly for the purpose of pumping water, with the Cheops pyramid playing a special role as a solar-powered water desalination plant. Since this point of view is still highly speculative, I will refrain from a detailed explanation here. Because the actually proven inventions and discoveries are already exciting enough…

Chinese documents from the year 20 AD also prove there the use of burning mirrors in religious ceremonies. The Jewish philosopher Philon of Byzantium (ca. 25 B.C. – 50 A.D.) used solar radiation in a thermoscope, the forerunner of today’s thermometer: a tube filled with air and sealed at the upper end was immersed with its lower end in the water of a container. If the tube is now exposed to solar radiation, the air enclosed in it expands and the water in the container rises. This idea was not taken up again until 1615 by Salomon de Caus (see below).

Also secured is a story from ancient Rome. A good 2,000 years ago, the guardians of the temple of Vesta – Vesta was the goddess of the heart – deliberately let the fire go out once a year, only to rekindle it with the concentrated rays of the sun from a conical metal reflector.

As early as the first century AD, water-filled, dark-coloured clay pots were in use in the Roman Empire, which heated the water on the roofs by the heat of the sun; and as early as 37 AD there are reports of a greenhouse in which the Emperor Tiberius’ favourite cucumbers were grown for him.

Around 100 A.D. the Mecanicus Heron of Alexandria (life data not exactly known) not only deals with steam power (Heronsball), with programmable water- and air-powered devices and musical machines, but also with a solar water heater.

In the following centuries it does not seem to have gone much further, and it is not until the Justinian Code of the 6th century that the passive use of solar energy is mentioned again, in the form of a building regulation establishing the individual right of access to the sun and preventing the casting of shadows on other beneficiaries.

Abu Saad al-Alaa Ibn Sahl, a Persian mathematician and physicist who worked in Baghdad during the Abbasid caliphate, at the height of Islam, wrote a treatise on burning mirrors and glasses around 984, which contains the first known correct form of the law of refraction. His texts are used after the turn of the millennium by Ibn Al-Haitham, who is even called one of the forefathers of solar energy at the MENASOL conference in Cairo in May 2010.

In the 11th century Roger Bacon worries about the Arabs who use burning mirrors in war. He tries to convince Pope Clement to build similar ‘ weapons’, but is imprisoned for his persistence. After all, the enemy could attack against the sun, at night or on cloudy days!

In Italy, the master builder Andrea del Verrocchio (1435 – 1488) uses burning mirrors to solder the copper on the dome roof of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral.

Around 1515, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), who had already been working on finding a clean source of energy for some time, began to build a huge reflector (some sources speak of a width of over 6 km!) to dry clothes. Among his many drawings is one in which a distant reflector directs its rays at an array of tubes…. possibly an early form of solar absorber.

In1560 the French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510 – 1590) had a solar oven made, but I have not yet been able to find out its purpose. And in 1561 the chemist and botanist Adam Lonicer (Lonitzer; 1528 – 1586) describes the use of mirrors in the use of sunlight for the distillation of perfume. The technique of producing olfactory essences by means of solar-heated water is said to have been widespread at that time, especially in Syria.

Around 1600, the production of glass panes was perfected in France. Exactly 10 years later Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) announced that he had discovered sunspots through his telescope – at the same time he got into trouble because of his heliocentric view of the world. The fact that the sun was at the centre of events was not what the church had in mind at the time. Chinese astronomers, however, had already described sunspots a good 2000 years earlier.

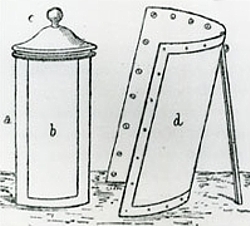

In1615, the French physicist and engineer Salomon de Caus (also Mondecaus, de Caulx, de Caux, de Cauls; 1576 – 1626), who is regarded as one of the many inventors of the steam engine, built two devices, which he also described in his art book. Using glass lenses that amplify sunlight and the resulting heating of water in a metal boiler, de Caus operates an air organ and what is probably the first solar-thermal water pump, with which he sets a small fountain in motion.

In 1646, the inventor of the magic lantern, the Jesuit Athanasius Kirchner (1601 – 1680), described in his work Ars magna lusis et umbrae various solar machines built by him (also for warlike purposes), and around 1690, Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus (1651 – 1708) produced a widely praised burning mirror with a diameter of 1.60 m in Dresden, which was used for experimental purposes in a pottery. It is now in the Lomonosov Museum in Moscow. Tschirnhaus (o. Tschirnhausen) also worked with large burning lenses.

From 1700 Holland leads Europe in the development and use of glass-walled greenhouses.

In1764, the French chemist and founder of modern chemistry Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) scientifically explains how an increase in temperature in a medium can also be achieved by means of solar radiation. In 1774 , he heated mercury in air, producing mercury oxide, which in turn was itself heated, recovering oxygen. For this purpose he uses a bell-shaped glass, the base of which is placed in a tub of water. The heating is carried out over 12 days – using a large glass lens which focuses sunlight through the glass onto the mercury.

In1765, the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc Buffon (1707 – 1788) succeeded in melting lead from a distance of 100 m by means of 140 plane mirrors. As early as 1747, he had succeeded in igniting a woodpile in the gardens of the French royal house from a distance of about 60 m, for which he had used 300 individual mirrors. At a distance of 6 m, the solar reflector was able to melt silver.

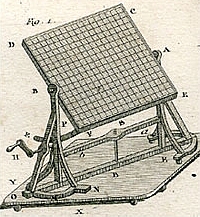

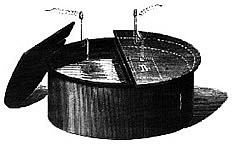

In1767, the Swiss scientist Horace-Bénédict Saussure (1740 – 1799) reached a temperature of 88°C (other sources even speak of 110°C) in his ‘capteur solair’, a construction of 5 glass boxes stacked on a blackened base. He developed a whole series of glass-covered solar catchers, which he also used for cooking, and is thus considered the inventor of the flat solar collector and ‘father of all solar cookers’.

In1770, French scientist Marc du Carla Bonifas optimizes Saussure’s solar cookers by adding insulation and reflective mirrors. In 1784, in the ‘Magazin für das Neueste aus der Physik und Naturgeschichte’, du Carla also described a ‘fire collector’: “The intention of this machine is to accumulate the heat of the sunandkeep it together in such a way that all strictly liquid matter can melt. (…) The sun’s fire of a fine spring day can bring a cauldron full of iron, more than a fathom in diameter, into flux.“

In 1772, Sir Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) uses a system of concave mirrors to focus solar rays. This system is later further developed by the Russian polymath Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (1711 – 1765) by using eight lenses and seven mirrors. Only two years later Lavoisier builds a solar furnace by means of two lenses of 20 and 130 cm diameter, respectively, with which he already achieves a temperature of 1,780°C.

Unfortunately, I don’t know the exact date of the miniature cannon shown here, which is fired at exactly 12 o’clock noon – solar ignited, of course. This beautiful sundial is made of brass, stands on a white marble base and has an adjustable lens. The overall diameter is only 22.7 cm.

It is certain that such a small sundial cannon is installed in 1786 in the garden of the Palais Royal and exactly on the meridian of Paris, where it announces the noon time on sunny days from May to October until 1914. A much larger acoustic sundial was installed in the fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña in Havana from 1774.

In 1800, the astronomer and musician Sir Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel (1738 – 1822), while guiding a thermometer along the coloured solar spectrum, discovers that the heat does not reach its maximum in the middle, but behind the red edge of the colour scale: in the infrared.

In1816, the Scottish priest Robert Stirling (1790 – 1878) applied for a patent for a hot-air engine, which was also used by Lord Kelvin (William Thomson, 1824 – 1907), among others, in his classes. After a long period of oblivion, the Stirling engine is now being used again in combination with solar parabolic mirrors.

In 1818,Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777 – 1855) revived the debate about the existence of extraterrestrial cultures by introducing the heliotrope, which he had invented. The heliotrope (Gr. facing the sun) is a solar mirror developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss that allows precise surveys over long distances by reflecting sunlight with a mirror towards a target. After the heliotrope proves its efficiency in the field of geodesy several times, Gauss plans to use a more advanced version of his device to advance the search for extraterrestrials: “With an amalgamation of 100 separate mirrors, each with an area of two square meters, good heliotrope light could be sent to the moon.”

British lawyer and astronomer Sir John Herschel (1792 – 1871), son of Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel, uses a solar cooker to prepare meals during an expedition to the Cape of Good Hope in 1830. The black-lined box of mahogany wood, buried in the sand for insulation, reaches a temperature of 116°C. The father, for his part, has a bowl of water heated by sunlight in 1837, thereby measuring the thermal output of our central star.

The photoelectric principle, which is the basis of all kinds of solar cells, is discovered in 1839 by the then only 19-year-old French physicist Alexandre Edmond Becquerel (1820 – 1891) – the father of Antoine Henri Bequerel (1852 – 1908), who will receive the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903 – for his discovery of radioactivity in 1896.

In1860, another Frenchman, Augustin Mouchot (1825 – 1912), a secondary school teacher at the Lyceum of Tours, began his first experiments on a solar cooker in order to reduce his country’s dependence on coal as a fuel – and by 1866, his solar-powered steam engine, patented in 1861 and the first ever, was in operation. With a surface area of 18.6m2 and a cone-shaped collector, it achieves 1.5 hp. The efficiency is around 3 %. The inventor also probably made the first parabolic trough reflector.

A. Mouchot presented his inventions to Napoleon III in Paris in 1866, who then gave him financial support. This enabled him to develop, among other things, a system for tracking the sun. In 1869, Mouchot also wrote the world’s first book on solar technology, Die Sonnenwärme und ihre industriellen Anwendungen (The Heat of the Sun and its Industrial Applications), and a second edition was published in 1879. However, a German translation of this work did not appear on the market until 1987 (almost 120 years later!!)…

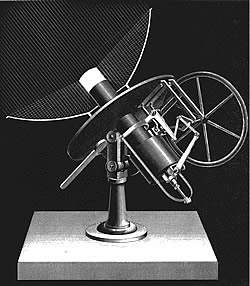

Also in the 1860s, the builder of the legendary warship Monito, and one of the inventors of the ship’s propeller, the Swedish-American engineer John Ericsson (1803 – 1889) began to develop measuring instruments for the quantitative detection of solar radiation energy. On Beach Street in New York, he sets up a research laboratory for solar energy on the top floor and in the attic.

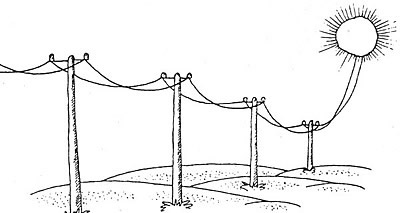

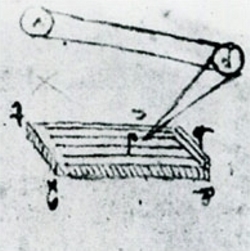

He had already built his first solar-powered hot-air machine in 1826, when he had become aware of the working capacity of solar energy. For over 50 years he designed solar grills and solar-powered steam and hot-air engines. His most famous, dating from 1870, is rectangular in shape (3.5 m x 2 m) and consists of narrow strips of glass, silver-plated on the outside and mounted on a parabolic base. In the focal line is a 15 cm diameter tubular steam boiler.

Around this time, the famous British engineer Sir Henry Bessemer (1813 – 1898) constructs a solar melting furnace 3 m in diameter with small flat mirrors, and uses it to melt copper and zinc. The Germans Stock and Heynemann are the first to use vacuum for thermal insulation and focus sunlight by means of glass lenses onto a melting crucible in an evacuated glass sphere. This enables them to melt silicon, copper, iron and manganese samples.

The proposal of the young French physicist, poet and inventor Charles Cros (1842 – 1888), who in a publication in 1869 suggested setting up an armada of gigantic parabolic mirrors all over Europe, also sounds daring and fantastic. On these, however, not sunlight but artificially generated electric light was to be directed, concentrated and then sent in the direction of Mars or Venus in order to make contact with the inhabitants of the planets there.

Around 1870 the two French engineers A. Mouchot and Abel J. Pifre joined forces and built solar cookers for the French troops in South Africa, as well as various solar machines. The collector of one of these machines is a parabolic mirror with a diameter of 2.20 m and has silver-plated copper plates on the inside. The tubular steam boiler at the focal point is blackened and drives a water pump. In Algeria, A. Mouchot tested various solar apparatuses on behalf of the French government in 1877/1878 in order to develop them as “energy sources for poor hot countries”, but in its report of 1880 the government judged solar technology to be uneconomical. After all, it still takes an hour to bake a pound of bread or boil two pounds of potatoes.

In1872, a team of technicians led by J. Harding and Charles Wilson builds the world’s first solar seawater desalination plant for the operators of a sodium nitrate mine in the Chilean Atacama Desert near the town of Salinas. It has a surface area of 4,700m2, a daily output of 24,000 litres and will operate for 40 years without any problems.

As early as 1873, Willoughby Smith (1828 – 1891) discovers that selenium changes its resistance when exposed to sunlight (photoconductivity). This is the first step towards the solar cell.

In 1876, William Grylls Adams (1836 – 1915), a professor at King’s College, London, and his student Richard Evans Day, found that selenium even ‘produces’ electricity when exposed to sunlight. A namesake, William Adams, working as a colonial official for the British Crown in Bombay, India, writes the award-winning and far-sighted work Solar Heat: A Substitute for Fuel in Tropical Countries during this period. He also patents an eight-sided solar cooker and builds a solar steam engine with reflector that produces 2 kW.

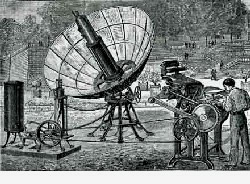

In 1878, A. Pifre‘s printing press fed with solar steam became particularly famous. During the Paris World’s Fair, 500 copies of Le Journal Soleil were printed every hour, reporting on the advantages of solar energy in general and on Mouchot’s research in particular. A. Mouchot himself, still an ardent advocate of solar energy, demonstrates a solar-powered steam engine with a conical burning mirror 5 m in diameter, the steam from which is used to power a refrigerator via a condenser. He also demonstrates a solar cooker that cooks a pound of beef in 25 minutes. The two inventors receive medals, but not the financial support they had hoped for. A. Mochot dies in Paris in 1912 – poor, lonely and forgotten.

In 1879, Heinrich Hertz uses Edmond Becquerel’s discovery to study the effect of light on solid matter.

A New York inventor named Charles E. Fritts builds the first solar cell in 1883, using a ‘wafer’ of the semiconducting selenium and a wafer-thin coating of a layer of gold. The efficiency is still less than 1 %. His corresponding statements are received with the greatest scepticism. C. However, Fritts sends some of his solar plates to Werner von Siemens (1816 – 1892), who is enthusiastic about them and presents the cells at the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He calls this a “discovery of the greatest scientific importance.” In the same year, Ericsson builds a parabolic trough collector from silver-plated glass plates with a total area of 9.3m2 and a blackened absorber tube in the focal line. However, the yield is only 0.7 kW.

Now begins a period with a flood of patents in the field of solar energy, although their realization occurs only in a few individual cases. In 1880 E. J. Molera and J. C. Derbrain receive the German patent for a solar boiler, and in 1882 and 1883 a W. Calver for his solar motors.

In 1885, the physicist Charles Tellier (1828 – 1913), known for his cooling technologies, is granted a patent for a non-reflective solar steam engine using ammonia as a working fluid, heated inside very flat collectors made of metal. Four years later he also published a proposal to use solar energy for the industrial production of ice.

Also in 1885, ‘Massachusetts pioneer’ Charles H. Pope, who also experimented with solar machines, summarized the ideas of his day on solar use in an article in the journal Scientific American.

1887 James Moser reported for the first time on a dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cell.

From 1888, the Russian physicist Aleksandr Stoletov researched the external photoelectric effect (photoconductivity in ultraviolet light), which had also been investigated by Heinrich Hertz in 1887. In 1889 Stoletov then developed the photocell, which was distinguished from the selenium cell primarily by its lower inertia and higher stability.

Also in 1888, Edward Weston was granted US patents Nos. 389,124 and 389,125 for a solar cell.

In1889 Wilhelm Hallwachs (1859 – 1922), an assistant of Hertz, works in Dresden on the further development of the photoelectric effect (Hallwachs effect).

In 1890, H. E. Wilsie uses the glass cover technique to heat sulfur dioxide and drive a motor with it. In this way he succeeds for the first time in ensuring continuous operation even in those times when the sun is not shining (see below).

In1891 a Clarence M. Kemp from Baltimore patented and marketed the first commercial solar water heater, The Climax. Several thousand of this collector are sold. Other sources say that already 6 years later it was in use in 30 % of all households in Pasadena.

In 1894 Melvin Severy receives the US patents no. 527.377 and 527.379 for a solar cell.

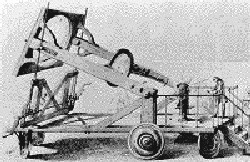

The principle of the solar tower is first patented in 1896 by C. G. O. Barr. A semi-parabolic mirror is mounted on a freight wagon which moves on a circular track to follow the sun and direct its focused rays onto a centrally installed boiler.

Kurt Lasswitz (1848 – 1919) describes in his novel Auf zwei Welten (On Two Worlds ), published in 1897, an energy-hungry Mars that therefore colonizes the Earth – and promptly sets up huge solar collector fields in the Sahara and Tibet. Particularly far-sighted: the means of payment of the ‘Martians’ is also energy!

In1897, Harry Reagan is granted US Patent No. 588,177, also for a solar cell.

In1898, the ingenious inventor Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943) builds his first apparatus for harnessing solar energy.

Aubrey G. Eneas, a Briton living in Boston, who founded the world’s first ‘solar company’ with his Solar Motor Co. in 1892, builds a solar power machine with 4 hp in 1901, including 1,788 mirrors in the form of a reflector more than 10 m in diameter, which pumps almost 5.5 t of water per day at peak times.

Built on an ostrich farm in Pasadena, California, the system weighs 4 tons and is 4% efficient. Eneas is having no luck with his machines, however: While his first system falls victim to a storm, the second is destroyed by hail.

At the turn of the century, many households in Arizona provide themselves with hot water by placing black water-filled barrels on their roofs, which reach a sufficient temperature by the end of the day so that the water can be used for bathing or washing up.